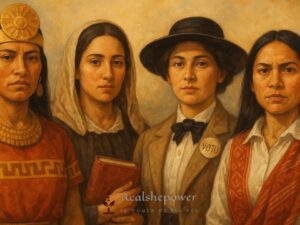

In the cloud-wrapped highlands of Chimel, a tiny Maya-K’iche’ village in Guatemala’s Quiché department, Rigoberta Menchú Tum was born on 9 January 1959 into a world where land, language and life itself were under siege. At 66 (as of 2025), she remains one of the most recognisable Indigenous women on earth — the first Indigenous person ever to win the Nobel Peace Prize (1992), the first to address the United Nations General Assembly in traditional dress and native language, and the living symbol of a people who refused to vanish.

She never attended formal school beyond a few months, yet she has received 37 honorary doctorates. She learned Spanish as her fourth language after K’iche’, Kaqchikel and Mam. And she turned the story of her family’s annihilation into one of the most influential human-rights testimonies of the 20th century.

Table of Contents

A Childhood Ended by Fire

Rigoberta was the sixth of nine children born to Vicente Menchú, a respected community leader, and Juana Tum, a traditional midwife. The family lived on a small plot in the mountains, growing maize and cardamom, but the best land belonged to wealthy landowners backed by the military. When Vicente joined the peasant union to demand land rights, the repression began.

Between 1979 and 1981, during Guatemala’s genocidal “scorched earth” campaign:

- Her 16-year-old brother Petrocinio was kidnapped, tortured and burned alive in front of villagers in Chajul square.

- Her father Vicente died in the 1980 Spanish Embassy fire in Guatemala City, when police set the building ablaze, killing 39 Indigenous and student protesters.

- Her mother Juana raped, tortured and left to die by soldiers in 1980.

Rigoberta, barely 20, fled to Mexico in 1981 carrying nothing but the clothes on her back and the stories of her people.

The Book That Shook the World

In exile in Chiapas, Mexico, she met Venezuelan anthropologist Elisabeth Burgos-Debray. Over one week in Paris in January 1982, Rigoberta dictated her life story in Spanish while a tape recorder ran. The result — I, Rigoberta Menchú (1983) — became an instant global phenomenon: translated into 23 languages, taught in universities worldwide, and credited with forcing the world to finally see Guatemala’s hidden genocide.

The book won the Casa de las Américas prize and sold over half a million copies in dozens of languages. Critics later questioned some details, but the UN’s 1999 truth commission confirmed the core truth: between 1960 and 1996, the Guatemalan state killed or disappeared 200,000 people — 83 % of them Maya — in what the commission classified as genocide.

Mayan People – Unveiling Their Ancient Secrets

Dive into the mystic history of the Mayan civilisation — exploring their culture, astronomy, architecture and the wisdom hidden in ancient ruins.

From Refugee to Nobel Laureate

Back in Guatemala, Rigoberta founded the first Indigenous political party (Winaq) in 2007 and ran for president in 2007 and 2011 — the first Indigenous woman ever to do so. She lost both times, but her campaigns normalised the idea of Maya political power.

In 1992, at age 33, she became the youngest person and the first Indigenous woman to win the Nobel Peace Prize. She used the entire $1.2 million prize money to establish the Rigoberta Menchú Tum Foundation, which has since:

- Built 35 schools in rural Maya communities

- Documented over 7,000 testimonies of genocide survivors

- Trained hundreds of Indigenous women as community health promoters and paralegals

- Successfully lobbied for the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (2007)

Still Fighting, Still Maya

In 2025, Rigoberta continues to live between Guatemala City and her village. She wears full traje (hand-woven Maya dress) every day, speaks K’iche’ at home, and refuses bodyguards despite repeated death threats. She serves as a UNESCO Goodwill Ambassador and chairs the Indigenous Initiative for Peace.

Recent victories include:

- Helping secure the 2023 conviction of former Guatemalan military officers for the 1982 Dos Erres massacre

- Leading the 2024 campaign that forced the Guatemalan Congress to recognise Indigenous midwives’ traditional knowledge in national health policy

- Launching a digital archive of Maya oral histories in 12 Indigenous languages

When asked how she survived so much loss, she answers in K’iche’ first, then translates:

“We Maya believe that when someone dies unjustly, their spirit becomes a seed. My family became seeds. My work is simply to water them.”

Rigoberta Menchú Tum never set out to become famous. She set out to make sure her people were no longer invisible and in doing so, she made the entire world look.

The Fiercest Activists Are Indigenous Women

A tribute to indigenous women around the world leading grassroots movements — fighting for land, rights, identity and collective survival with courage.